¶¶ŇůĘÓƵ throughout the decades

1909-39

A Sort of Foreign Office

1939-68

Punching Above Our Weight

1968-84

New Guys with New Ideas

1984-2008

Integration and Globalization

1909-39: A Sort of Foreign Office

1939-68: Punching Above Our Weight

1968-84: New Guys with New Ideas

1984-2008: Integration and Globalization

A Sort of Foreign Office: 1909 to 1939

Frustrated by the backlog of Canada-United States issues that occupied much of his time, the British ambassador to Washington, James Bryce, suggested in 1908 that Canada needed "a sort of Foreign Office." Taken up by Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the idea led to the creation of a small Department of External Affairs in June 1909. Laurier's successors as prime minister, Robert Borden and W.L. Mackenzie King, assumed direct responsibility for the fledgling Department, which played an important part in Ottawa's efforts over the next two decades to exercise greater control over Canada's relations with the world.

An early proponent of a separate ministry to coordinate Canada's "external affairs," Sir Joseph Pope served as the Department's first under-secretary, from 1909 until 1925.

(Source: William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-110845)

The East Block of the Parliament Buildings served as the Department's headquarters from 1914 until 1973.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, PA-009423)

Just as they are today, cross-boundary issues such as Arctic sovereignty were among the new Department's priorities.

(Source: Vancouver Province, February 1, 1912)

Prime Minister and Secretary of State for External Affairs Robert Borden (seated fourth from left) at the 1917 Imperial War Conference in London. Canadian sacrifices during the First World War drove Borden to seek greater control over Canada's foreign policy.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, C-000241)

O.D. Skelton joined the Department in 1925 as its second under-secretary and set out to establish a professional foreign service. Here, Skelton (left) is shown en route to Europe in the early 1930s with one of his first recruits, the young Lester B. Pearson.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, PA-117595)

The Canadian delegation to the 1926 Imperial Conference in London secured the right of former British colonies to an independent foreign policy and their own missions abroad. Left to right: Minister of Justice Ernest Lapointe, Prime Minister and Secretary of State for External Affairs W.L. Mackenzie King, industrialist Vincent Massey, and Peter Larkin, High Commissioner to the United Kingdom.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, C-001690)

The Department opened legations in Washington, Paris, and Tokyo in the 1920s. Shown here in 1929, in full diplomatic dress, is the staff of the Canadian legation in Tokyo. From left to right: K. P. Kirkwood, H. L. Keenleyside, Sir Herbert Marler, and J. A. Langley.

(Source: Ueno Makita Kogabo/Library and Archives of Canada, PA-120407)

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought Prime Minister R.B. Bennett to office, where he turned to the Department to put into action a trade-focused agenda. Bennett (middle) is shown greeting the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin (left), on his arrival in Ottawa for the 1932 Imperial Economic Conference.

(Source: Library and Archives of Canada, C-81448)

Prime Minister and Secretary of State for External Affairs W.L. Mackenzie King faced the threat of war as Fascism advanced across Europe and Asia. His cautious foreign policy, designed to avoid divisive debates within Canada, often frustrated the Department, which was anxious to expand Canada's diplomatic reach.

(Source: John Collins, The Gazette [Montreal], April 24, 1939)

With the country united behind him, Prime Minister and Secretary of State for External Affairs W.L. Mackenzie King petitioned King George VI for a declaration of war on September 10, 1939. By waiting a full week after Britain declared war, King underlined Canada's complete control over its own foreign policy and set the stage for Canada's war effort.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada)

Punching Above Our Weight: 1939 to 1968

The outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1939, transformed the Department of External Affairs. From six missions abroad in 1939, the Department expanded across the globe, encompassing 26 foreign missions by 1946 and more than 93 by 1967. War brought the Department additional responsibilities, opened up opportunities for women within the Department, and prompted Canada to take on new international roles. By war's end in 1945, the Department had embraced an active internationalism that would define Canadian foreign policy for a generation.

The war had an immediate impact on Canadian diplomats and their families in Europe, where the German blitzkrieg of May 1940 forced many to flee under harrowing circumstances. Shown here, circa 1941, is Canada House in London, surrounded by the rubble from a recent bombing raid.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, e008319469)

The war led to a national labour shortage, forcing the Department to hire qualified women to do the work of junior officers. The women, however, remained ineligible to become foreign-service officers until 1947. Shown here, in the early 1940s, is Agnes McCloskey (foreground).

(Source: Yousuf Karsh/Library and Archives Canada, PA-187411)

Norman Robertson became under-secretary in 1941. Shown here is Prime Minister and Secretary of State for External Affairs W.L. Mackenzie King (right) in 1944, he reorganized the wartime Department, turning it into an arm of modern government for the first time.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, C-015134)

The UN was at the heart of Canada's post-war diplomacy. General A.G.L. McNaughton (left) became Canada's first permanent representative to the UN in 1948. He is shown here (left to right) with Transport Minister Lionel Chevrier and diplomats Charles Ritchie and John Holmes.

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada/Maurice Zalewski/Library and Archives Canada, PA-187127)

The UN proved an insufficient guardian of international security in the face of Communist aggression in the 1940s. One of the first Western democracies to seek a regional security pact, Canada played a leading role in negotiating the North Atlantic Treaty. Hume Wrong, Canadian ambassador to the United States, signed the treaty for Canada in April 1949.

(Source: Harris-Ewing/Library and Archives Canada, PA-124427)

During the 1950s, changing social attitudes and the Department's expansion made it possible for women to move up the Department's ranks. Elizabeth MacCallum became Canada's first woman head of mission when she was appointed chargé d'affaires in Beirut in 1954.

(Source: Richard Harrington/National Film Board of Canada/Library and Archives Canada, PA-112766)

The growth of the Department in the 1950s created an influential foreign ministry capable of "punching above [its] weight," in the words of Lester B. Pearson. In this photo, Pearson, secretary of state for external affairs, holds a press conference during the Suez Crisis of 1956. Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his role in resolving the crisis.

(Source: Duncan Cameron/Library and Archives Canada, PA 155557)

Jules Léger (left), who became the Department's first francophone under-secretary in 1954, with Sidney Smith, secretary of state for external affairs from 1957 to 1959.

(Source: Library and Archives Canada, PA-214179)

Howard Green, secretary of state for external affairs from 1959 until 1963, became a passionate advocate of nuclear disarmament. He is shown here in November 1959 addressing the UN on the effects of atomic radiation.

(Source: UN Photo)

Diplomat Blair Seaborn raises the flag at Canada's mission to the International Commission for Supervision and Control (ICSC) in Vietnam, February 15, 1965. Between 1954, when Canada joined the peace commissions in Indochina, and 1973, when the final mission withdrew, almost a third of the Department's diplomats served in this war-torn region.

(Source: Seaborn Collection)

Paul Martin, Sr., who served as secretary of state for external affairs from 1963 until 1968, is shown here greeting probationary foreign-service recruits in 1967.

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada)

New Guys with New Ideas: 1968 to 1984

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau came to power in 1968 with new ideas about diplomacy and Canada's role in the world. He launched a detailed review that put domestic considerations at the centre of Canada's foreign policy and streamlined the government's international operations. In March 1980, the process of consolidation began in earnest when the Department was given responsibility for delivering the country's foreign aid and immigration programs abroad. Two years later, in January 1982, Trudeau announced the creation of one department, later known as the Department of External Affairs and International Trade, charged with all foreign trade and traditional foreign-policy functions.

The tough diplomatic challenges of the 1960s, which included Castro's Cuba, the unpopular American war in Vietnam and trouble with France, sparked criticism and cries for reform from across the political spectrum. The caption reads: "Some gentlemen here volunteering their services as foreign affairs advisors. ...Also, a Mr. Allen Dulles called and intimated that he was available."

(Source: Ed Uluschak, Edmonton Journal, April 26, 1968)

While Prime Minister Trudeau sometimes criticized the Department, he gradually came to appreciate its expertise. Canadian diplomats, for instance, played a vital role in negotiating the terms of Canada's recognition of Communist China in 1971, an important Trudeau objective. In this photo, Arthur Menzies, ambassador to the People's Republic of China, promotes Canadian technology at a Beijing exhibition in 1978.

(Source: Arthur Menzies)

In June 1979, Prime Minister Joe Clark appointed Flora MacDonald as secretary of state for external affairs. The first woman to hold the post, she is shown here at a press conference with Canada's ambassador to the UN, Bill Barton, in September 1979.

(Source: UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata)

Pierre Trudeau's government placed a premium on asserting Canada's sovereignty, an area where the Department of External Affairs excelled. Canadian diplomats participated in the complex negotiations that eventually produced the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982. As a result, more than one million square miles were added to Canada's territory. Legal Advisor Alan Beesley (shown in 1981) played a key role in these negotiations.

(Source: UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata)

Under Prime Minister Trudeau, the Department launched an ambitious program of embassy construction designed to project Canadian culture and values abroad. Opened in 1981, Canada's embassy in Mexico City was the first of several new embassies intended to serve as both a traditional diplomatic mission and a cultural centre. Other recent embassy buildings pictured here include:

Washington (1989),

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada)

Tokyo (1991),

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada)

and Seoul (2007).

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada)

In January 1982, the Department of External Affairs and the Trade Commissioner Service were combined into a single trade and foreign-policy ministry, with a broader mandate. Here, Secretary of State for External Affairs Allan J. MacEachen confronts the vexing challenge of multilateral trade.

(Source: Ed Franklin, The Globe and Mail, November 26, 1982)

Integration and Globalization: 1984 to 2008

Pierre Trudeau's reforms have endured, though not without controversy. The government's deficit-fighting policies under prime ministers Brian Mulroney (1984 to 1993) and Jean Chrétien (1993 to 2003) constrained the Department's operations and obliged it to focus on its core functions. In 1992, the Department shed its responsibilities for aid and immigration, a return to basics that was partly reflected in its decision to change its name, in 1993, to the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. In 1995, Parliament recognized this change, encouraging the Department to focus on what it does best, and on what it has done well for 100 years; advancing Canadian interests abroad.

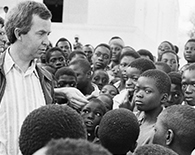

Following the election of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in September 1984, Joe Clark was appointed secretary of state for external affairs. The elimination of apartheid in South Africa remained a priority for both Mulroney and Clark, who is shown here taking a break during the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Zambia, 1987.

(Source: Commonwealth Secretariat)

Canadian diplomatic representatives abroad are active in their local host communities in a number of different ways. Shown here are participants in the annual Terry Fox Run, a uniquely Canadian event that raises money for cancer research. Canada's ambassador to Japan, Robert Wright (centre), joins embassy staff and Japanese participants in the 2004 run, with the Tokyo cityscape in the background.

(Source: Embassy of Canada in Tokyo)

Canadian diplomats "in action": securing nuclear and radioactive material in Russia (2005),

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, Mark McLaughlin)

helping to repair Haiti's fragile social fabric (2006),

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, Mark McLaughlin)

evacuating Canadians from the war in Lebanon (2006),

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, Yasemin Heinbecker)

and promoting Canadian exports in China (2007).

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, Yasemin Heinbecker)

Since the 1980s, the Department has spearheaded Canadian efforts to exploit the opportunities available in the new global economy. Here, in January 2008, International Trade Minister David Emerson and Swiss Federal Councillor Doris Leuthard sign a free-trade agreement between Canada and the four countries of the European Free Trade Association.

(Source: Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada)

Young foreign service officers help evacuate Canadians from war-torn Lebanon in July 2006. The Department is actively recruiting a new generation of foreign service officers as it renews itself to confront the challenges of its next century.

(Source: David Foxall)